Rare Rides Icons: The Lincoln Mark Series Cars, Feeling Continental (Part VIII)

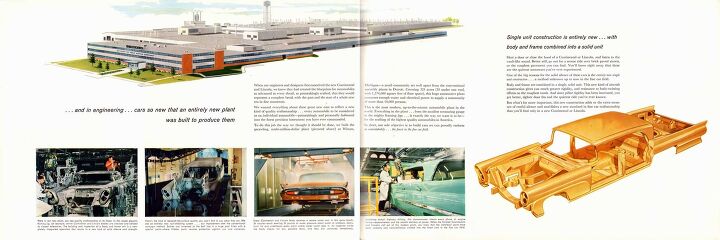

With the Continental Division dead, a cost-weary and (newly) publicly traded Ford Motor Company headed into the 1958 model year determined to unveil a solid luxury car showing against its primary rival, Cadillac. However, the “Continental Mark III by Lincoln” was a Continental in name only: It wore the same metal and was produced at the same new factory, Wixom Assembly, as the rest of the Lincoln models (Capri, Premiere) that year.

Brass at Ford hoped the Continental name on the Mark III would make customers believe it was something special, like the Cadillac Eldorado with which it competed. As mentioned last time, aside from its Continental name, the Mark III for 1958 used One Simple Trick to lure buyers into its leather seats: a Breezeway window. First up today, pricing problems.

Not a problem at Ford generally, but rather pricing within the small Lincoln lineup given the identical engineering and almost identical looks of the three cars on offer. The most basic Capri asked $4,803 ($49,087 adj.) that year, while the better equipped Premiere was $5,483 ($56,037 adj.). However, the Mark III was $6,283 ($64,213 adj.) before options. Recall the original directive at Continental Division was to sell a Mark III for $6,800 ($68,739 adj.), which ballooned to $9,800 ($99,065 adj.) after the original car was developed. At its 1958 ask, the Mark III was about 37 percent cheaper than the hand-assembled 1957 Mark II.

And while that sum was cheaper than the likes of the new Eldorado Biarritz convertible at $7,500 ($76,651 adj.), the Biarritz was considerably more desirable than the over-the-top 1958 Mark III. By the way, the average American household income in 1958 was $4,600 ($47,012 adj.).

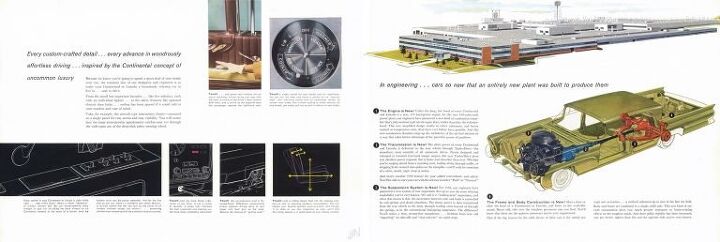

Part of the problem was the development cost of the 1958 Lincolns. Ford decided to switch its luxury arm from body-on-frame construction to a unibody that year. The new Lincolns were very large for a unibody car (perhaps the largest to date), and Lincoln lost over $60 million ($613,208,391 adj.) in the period between 1958 and 1960. A big part of that was product development.

But just as the new Lincolns debuted and the domestic luxury car class got larger, heavier, and more expensive than it had been in some time, there was a big recession. The global Recession of 1958 proved itself a fast, sharp downturn. It ended up as the biggest recession in the post-WWII economic boom from 1945 to 1970.

One of the leading factors of the recession was a steep decline in new car sales. 1958’s sales figures were down 31 percent over the prior year. Automakers rode a high of 8 million US sales in 1955, but that slumped to 4.3 million in 1958.

The middle class started to hold onto their cars en masse in 1958, instead of trading for a new one. During 1958 Lincoln produced only 20,179 cars, which was down 36 percent over 1957. Ford itself was down 38 percent that year, compared to a 22 percent drop for Chevrolet, and a 45.1 percent decline at Plymouth.

It turned out to be the wrong time to dump a bunch of development money into a new unibody design, but Ford wasn’t to know that. The new 131-inch wheelbase on the 1958 Lincolns and their enormous and overworked bodies made them some of the largest cars on the road. Lincoln was bigger than a Cadillac, bigger than an even an Imperial (the brand that usually came with the most length).

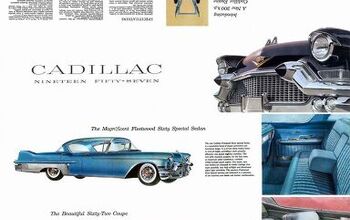

Capri, Premier, and Continental Mark III all had identical length, width, and height in 1958. All were 229 inches long, 80.1 inches wide, and 56.5 inches high. In comparison, the more prestigious Eldorado in Series 62 guise was 222.1 inches overall, and 80 inches wide. Even the Sixty-Special four-door reached only 225.3 inches in the final year of its sixth-gen guise for ’58. The D-body Imperial of 1958 came up a bit short, at 225.9 inches and 81.3 inches in width.

The Lincoln lineup rode on a wheelbase that was five inches longer than the year before, and the Capri and Premiere were about 4.5 inches longer than they were in 1957. Despite the increase in wheelbase and exterior dimensions in all directions, that didn’t always translate to an increase in interior measurements. For example, in a standard Premiere leg room decreased by nearly half an inch up front, while hip room decreased by 0.7 inches.

Shoulder room increased for front passengers in the ’58 Premiere, but rear passengers had less headroom. Gains from the unibody transition were seen mostly in increased shoulder room for all occupants. In fact, the shoulder room set a record in 1958 (63.1″ up front, 63″ in rear) that has never been bested by a passenger car to date.

As one might expect, the enormous new Lincoln lineup weighed a lot. The lightest two doors with a minimum of equipment weighed in at 4,900 pounds, while a fully-equipped Continental Mark III toured the country with 5,200 pounds of heft.

All Lincolns shared the same 430 cubic-inch (7.0 liters) MEL series V8. MEL stood for Mercury-Edsel-Lincoln, an engine family developed as the replacement for the Y-block Lincoln engine in production since 1952. The MEL featured wedge-shaped combustion chambers, and its piston determined the compression and combustion chamber shape. That was an engineering choice common to other V8 engines introduced at the end of the Fifties. An OHV design with two valves per cylinder, the MEL was built in displacements of 383, 410, 430, and 462 cubic inches.

The 430 version of the engine was fitted to all Lincolns from the 1958 to 1960 model years. Attached to the large V8 was the MX version of Ford’s three-speed Cruise-O-Matic, which was branded as the Turbo-Drive under Lincoln usage. The three-speed wrangled 375 horsepower in 1958.

Body styles for the Continental Mark III included a two-door hardtop, a four-door sedan, and a four-door hardtop that received a special name: Landau. The only body style exclusive to the Continental was a convertible. That halo model was the most expensive, and proved to be unique: It was the only time a Mark series car was offered as a factory convertible. The importance of the Breezeway as a distinguishing feature could not be overstated, as it was even engineered into the convertible version of the Mark III.

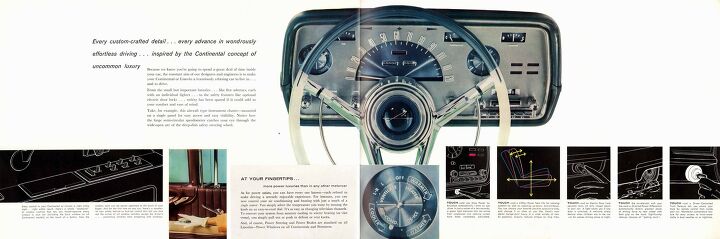

Options on the 1958 Continental Mark III were limited but included an FM radio to add to the standard AM band that cost around $125 ($1,277 adj.). Air conditioning was an optional extra for the big spenders. Also optional on the Continental was a system exclusive to Lincoln and Mercury cars, and only offered in the late Fifties: Auto-Lube! What a great name for a feature.

Its full name was Automatic Multi-Luber, and it asked the driver to press a button when things needed to be slippery. More specifically, a dash-mounted button marked Auto-Lube controlled the distribution of grease from a reservoir under the hood. Said reservoir was used to lubricate the necessary components in the more complex suspension systems of late-Fifties cars. The system was developed by Ford and Lincoln Industrial Corporation (not related), the latter of which invented the lever-operated grease gun.

Think of all the ball joints, springs, arms, tie rods, etc. that were part of an independent suspension design – no solid axles here! All those parts had grease fittings and needed to be greased repeatedly to prevent wear and the unpleasant sounds that happen where there’s not enough lubrication. This was the time before the grease in your ball joint (or similar) lasted the life of the component.

For the non-luxurious motorist, visits to a mechanic with a grease gun were required at rather short intervals. But the 1958 Lincoln driver could keep on going with Auto-Lube. When the button was pressed, a system of lines underneath the Lincoln delivered grease to every grease point in the front suspension. When the process was completed, a green light on the dash told the driver all was A-okay.

It was recommended the Lincoln driver remember to press the button once a day while the car was in operation. Each grease container would make up to 300 applications of grease to the front suspension. The system did not remain on offer for very long, but it’s interesting to consider what might happen to the lines as they sat with grease in them for a few years.

Lincoln could’ve used some grease to help slide cars out of showrooms in 1958 as sales tumbled. However, even with the recession, the Continental was the volume seller of the brand: 62 percent of Lincolns in 1958 were Mark IIIs, a total of 12,550 examples. That figure was composed of 1,283 standard sedans, 5,891 Landau sedans, 2,328 hardtop coupes, and 3,048 of the flagship convertible.

Lincoln headed a different direction in 1959 that would see a “new” Mark take the stage, and introduce a new name we all know today: Town Car. We’ll start there next time.

[Images: Ford]

Interested in lots of cars and their various historical contexts. Started writing articles for TTAC in late 2016, when my first posts were QOTDs. From there I started a few new series like Rare Rides, Buy/Drive/Burn, Abandoned History, and most recently Rare Rides Icons. Operating from a home base in Cincinnati, Ohio, a relative auto journalist dead zone. Many of my articles are prompted by something I'll see on social media that sparks my interest and causes me to research. Finding articles and information from the early days of the internet and beyond that covers the little details lost to time: trim packages, color and wheel choices, interior fabrics. Beyond those, I'm fascinated by automotive industry experiments, both failures and successes. Lately I've taken an interest in AI, and generating "what if" type images for car models long dead. Reincarnating a modern Toyota Paseo, Lincoln Mark IX, or Isuzu Trooper through a text prompt is fun. Fun to post them on Twitter too, and watch people overreact. To that end, the social media I use most is Twitter, @CoreyLewis86. I also contribute pieces for Forbes Wheels and Forbes Home.

More by Corey Lewis

Latest Car Reviews

Read moreLatest Product Reviews

Read moreRecent Comments

- Rochester I recently test drove the Maverick and can confirm your pros & cons list. Spot on.

- ToolGuy TG likes price reductions.

- ToolGuy I could go for a Mustang with a Subaru powertrain. (Maybe some additional ground clearance.)

- ToolGuy Does Tim Healey care about TTAC? 😉

- ToolGuy I am slashing my food budget by 1%.

Comments

Join the conversation

@conundrum--Being 70 I do have more than an idea of what life was like in the 50s and 60s and what a big deal it was to have a gravel road asphalted but I did not know about the existence of leather gaiter or any automatic or pre lube systems from the 50s. I have a lot of experience with vehicles I have owned with grease fittings and greasing them and yes I remember when sealed suspension parts became more popular. The last vehicle I owned that had grease fittings was a 99 Chevy S-10 and I actually prefer having grease fillings because the part being greased usually lasts longer. As for TVs my family mainly had 1 TV which was black and white until the early 70s when we got a color console and by the mid 70s we got an Amana Radar Range (microwave) which was expensive for the time and large and heavy. I also remember having to defrost the refrigerator, my mother having to iron clothes before permanent press fabrics, the bread box in the kitchen, the outdoor clothes line which everyone had, party lines,most people having just 1 car, and my grandmother's wringer washer. Most of us don't realize how far we have come and there are a few of us on this site that are old enough to remember the 50s, 60s, and 70s and with each of these eras there was the good and the bad but at least people were not glued to their smart devices.

I'm so old that I remember having to get up, walk over to the TV and manually change the channel. Talk about hardship. Growing up in Toronto we received signals from 6 TV stations. CBC, CTV, CHCH (an independent in Hamilton), and the NBC, CBS and ABC signals from Buffalo. In the late 1980's in the UK they still received less than a half dozen stations. But back then when you bought an appliance you expected it to last. Yes it might need repairs but getting 25+ years from a fridge and 30+ years from a stove was expected. TV's were more problematic. But how many TV repair shops still exist? Or appliance repairs? Our TV repair person taught that subject at the local college. That course/program was cancelled decades ago. Now throw out and replace. So much for 'ecology'. I used to change the oil on our early 1980's Hondas a minimum of 4 times per year. And lubed/greased all the 'fittings' and changed the air cleaner at the same time. Simple and quick to do. They may have been the last vehicles that I owned that required regular 'lube jobs'.